What to Expect

So many people hear the stories of “miracle” responses to NF and assume that’s the norm. The reality is that consistent work, as you have provided, over time is what tends to produce lasting results. Anything that forces you to learn something new tends to activate the brain.

It’s always important to remember that the training is for the brain–not the trainer. The brain is getting the feedback, which in many cases the mind can’t make head nor tail of–much less the trainer. When you do psychodynamic psychotherapy with a client who wants to break a habit, you recognize that you may have to change other things before the habit changes. Just telling the client to stop smoking, for example, or how bad it is for him, etc. simply doesn’t do the trick. So if you measure the number of cigarettes he smokes each day, you both may get frustrated because the number doesn’t go down for a while. If you look at the larger picture, the client may notice that he is less anxious, that he doesn’t get irritated as easily or other things which are laying the foundation for the final result. What measurable changes (outside of plain old performance) would you see when someone was suddenly able to ride a bike who couldn’t before.

Sure, a runner checks his heart-rate during exercise to see if he’s in the training range. That’s feedback for the heart. Seeing the graph rise or the movie play or whatever is feedback relative to training range for the PFC with HEG. I don’t know of any runners who graph their heart-rates from session to session. They may graph how far they were able to run, how quickly they ran, etc., but those are again performances.

If you assume that there is a stable situation in your brain (unlike any other part of your body) and that if you checked the ratio of red/infrared blood and its relationship with infrared temperature in the same spot, even at the same time every day it wouldn’t vary, I think you’d be quite disappointed. Even going to the gym or jogging you have probably noticed that some days it’s easy; some days it’s hard work. Thousands of things affect that relationship (which, by the way, is kind of a derivative), like how well you slept last night, when you last ate, how much you ate, what kind of mood you are in, what you’ve been doing for the last hour, etc.

The objective is to teach those brain areas to activate physiologically upon demand, from wherever they are when you start, and to be able to sustain that activation–improvement in stamina–over longer and longer periods. I’m not sure how you measure that over time except by saying, “I feel happier.” “I focus better for longer periods.” “I have greater control of myself.” “I’m planning and organizing more effectively when that’s appropriate.” etc.

Taking a Snapshot

When you do an assessment, QEEG or whatever, you are taking a snapshot of someone jumping on a trampoline. You can probably tell if they look excited or scared, what they’re wearing that day, maybe what the weather is like. But you don’t know if they’re at the top of their jump or the bottom, going up or going down, if this was a really big jump or just a little one, what kind of trampoline it is, etc. Taking multiple pictures will likely give you a lot of images that don’t necessarily look the same–especially when they are separated by time.

If you have a client come to you and complain, “my theta/beta ratio is all out of whack; I want to fix that,” then you should certainly train that and track that and do pre and post, etc. Don’t hold your breath waiting for that person to arrive in your office. Much more likely the client will want to feel safer or happier, be able to recall read or heard material after one contact with it, get along better with others, play golf better, or whatever. Real world stuff.

I know it’s disappointing when the client has gotten better as he wished as a result of the training and you just can’t “see it” on the EEG. Even QEEG’s, with thousands of measures of brain activity, don’t necessarily show “improvement” in the EEG.

Sorry. You’ll just have to be satisfied with pleased clients. (BTW, imagine a situation where the EEG looks dramatically better after 20 sessions–and the client is still struggling as much as he did when he came to you–do you think he’s going to care much about the EEG graphs?)

Charts versus Life

Most people want to become less anxious, or pay attention better, or sleep more effectively, or stop obsessing over things or whatever. If they are showing better average scores in their sessions, but those things aren’t changing, do you really think you can convince them the training is “working”?

The problem with using scores is that, depending on what designs you are using, chances are the targets are reset at the beginning of each session, and some may even be in automatic mode, so the points won’t necessarily change from session to session regardless of how well your brain is changing.

Back in the early 90s, when I began training with Joel Lubar as my mentor, he used % success as a measure that made really nice graphs over a series of sessions. In order for that to work, though, we had to set a target for theta and another for beta at the beginning of training–in the first session–and leave those targets stable throughout 20-40 session. Some days the brain would be so far away from the target that the client got virtually no feedback and the session was relatively useless; other days he was scoring 90% of the time or more, and again there wasn’t much “learning” involved in the session.

If you focus on those real-world things you want to change, set objective measures for them and track those week by week, you’re likely to have a lot more useful assessments of success.

One of the great disappointments that many have when starting to do QEEG’s is that–even with all that data and analysis–if you look at pre and post Q’s of someone who has made significant, widely-recognized changes, you often can’t identify exactly how the brain changed. I suppose you could take a series of very sophisticated measurements of the body of a child as she made several attempts to ride a bicycle, and I’ll bet you wouldn’t be able to identify what changed between the last failure and the first success–maybe not even between when she couldn’t ride and after she’d been riding for a month. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

I understand that there are many people in the field who are dying to have the graphs and the numbers, and I don’t begrudge them that. I spent lots of time in my early years looking at that stuff, long enough to convince myself that there was a poor registration between the numbers and what I cared about. Too many false positives (great graphs that didn’t result in change) and false negatives (horrible graphs in clients who made dramatic changes). So I stopped spending my time on that. You may be right that until you have trained enough people to see into the mystery of what is happening, had enough successes to trust the process, and gained some confidence (often as a result of training your own brain!) you really want those numbers as a way of convincing yourself you’re not a charlatan. And it may be, as Dale suggested, that the numbers can be motivational for some clients and trainers.

Graphing Progress

I’ve also seen lots of people who got so wound up in the tracking and judging of their “progress” that they got frustrated when they “weren’t making any.” Not all progress is graphable. And it’s not, in my experience, necessary to cognitively interact with a process to have it be beneficial. Meditation, for example, goes the other direction and has many of the same effects.

For my money, a client who starts the walking program and finds pleasure in it and does it for fun is at least as likely to continue it long term–much less likely to become obsessive about it–and, as we both agree, probably equally likely to benefit from it, even if he can’t explain how or why.

I got an email the other day back-channel from someone worried about my anti-scientific bent as relates to NF and my tendency to avoid getting all involved in tracking. For those who don’t already know this, I have an MBA in Finance and Economics from Northwestern, so I’m not in any way unfamiliar with the concepts of tracking numerically. But I also spent a dozen years doing turn-arounds in hospitals for a large hospital management company–my real preparation for doing NF. In those situations I learned that watching the numbers many of my bosses and colleagues missed the really important things happening around them. Enron had great numbers right up to the day when it imploded, because people there focused on the numbers. And there are hundreds of companies that make superb products, compete effectively, take care of their clients and workers and don’t ever achieve those “great numbers” because that’s not what they focus on. That I guess is my point: focus on what you want to change.

Changing Performance, not Data

It should be possible to conceive–even to a scientist who wants hard objective data (though quantum physics, which I think qualifies as a rather advanced science, seems to suggest that ALL of what we perceive as reality is actually quite subjective)–that the exercise itself is the outcome. My wife has plantar fasciitis in her foot. She does stretching exercises every day, and it is improving. What do we measure to be “scientifically certain” that she is getting better, or that there is some relationship between the stretching and the improvement in function? I don’t know. The MD doesn’t know. My wife doesn’t care.

In the same way, when I trained for improved ability to stay focused on sequential tasks years ago, I didn’t seek to change my personality. I didn’t want to switch from an artist to an accountant. I was simply improving my range, so that I was able to shift into and sustain for longer periods of time a state of higher activation that allowed me to do those tasks. I intuitively understood that there might well be a difference in some brain measures between my steady state and my ability to activate when desired. The one was easily measured in an assessment; the other perhaps not.

The part of my EEG I was training (theta/beta ratio) didn’t change very much. It’s still “high” for an adult. But what I can do with my brain changed, and how long I can do it changed. It’s possible that if I wanted to do an fMRI or a full QEEG to measure what my brain did at task, I’d see the changes. Frankly (maybe because I have a healthy dose of slow-wave and alpha activity) it was never worth the time, trouble or expense to me.

I didn’t train to change my brain. I trained to change my performance. Training the brain was the medium, just like my wife’s stretching exercises, just like doing aerobics to change stamina. Or taking medications that have never been clincally proven to have an effect on a particular problem (off-label uses) to change that problem.

Thoughts on Measuring Progress

Two women start jogging together. One keeps track of miles run, average speed, calories burned, graphing the results from day to day. The other just goes out and runs alongside her friend. Which one gets in shape faster? Which one better?

It is perfectly possible and valid for someone to do something with a specific goal in mind. It’s also possible to do something and SEE what happens. Since my instructions are “don’t think, don’t try, don’t judge”, obviously I’m in favor of the observer state. Since you want to have a target (which I can’t give you) and “do whatever it takes” to get there, asking you not to “try”, and certainly not to “judge” won’t really work very well. Maybe people with central PFC ratios in the 140 range have to do it that way. So set your own goals and see how you respond in the real world as you move toward them.

Or try doing as I suggest, hard as it may be, and see where that takes you.

Handedness

Way back in the 90s the Othmers did a nice little study where they took a group of children and measured everything they could think of to measure on them prior to training, then measured again post training. It between they simply trained C3/A1 and C4/A2 per their (at that time) standard ADHD protocol.

One of the things that struck them in the pre data was that, while in the general population about 92% are right-handed, among the ADHD kids, about 50% were right-handed, about 30% were lefties and 20% were mixed dominant. Dominance is one of the relatively early decisions a brain makes as it matures, since it allows the brain to divide functions and work more efficiently. “ADHD” is essentially a label for delayed brain maturation (which is why people so often say, “he acts younger than his age.”)

Following the training, the post findings showed, as I recall, that around 85% of the same group were now righties and the other 15% were lefties. None were still mixed dominant. In other words, up to 15% of the left-handers had become right-handers with no other intervention and all the brains had “picked a side” to be dominant for language which allowed them to become better organized, more efficient and more mature–less ADHD. That was without BrainGym or Interactive Metronome, though the exercises used in those systems can be helpful as well.

Placebos

There have been dozens of studies which used “the enormous power implicit in hooking somebody up to machines… or the relationship…the attention paid to the person” with control and training groups to clear those variables. Anyone who’s done much NF can tell plenty of stories of the client who was totally disinterested and fought the training every step of the way until he suddenly realized he had changed–and others who had fabulous relationships with the trainer who was super motivated to help them…and nothing happened. I’m simple in my old age: If the change results from a placebo effect, and it lasts, I’m happy to have it. My goal is exactly one: help the client change the things he/she wants to change in his/her own life. It doesn’t matter a lot to me how he happened to get to where he is when we start; it doesn’t matter a lot to me what it was that opened the door and let his brain shift. If it happens, we’ve met our goal, and I’m happy.

Proving Results

It over-simplifies things to refer to professionals as being charged with the responsibility of demonstrating effectiveness in some objective manner rather than just the subjective response of the client. The physicians who pile multiple psychoactive medications into young children with absolutely no research basis and no idea whatsoever what the long-term effects might be: what “objective demonstration of effectiveness” do they use? Are things changed so much since I came down to Brazil that physicians are now doing neurotransmitter panels pre and post medication to demonstrate that the “out-of-balance” neurotransmitters have now “normalized”? And if so, how does it happen that so many children “need” a stimulant, an anti-depressant, an anti-convulsant and maybe a good anti-psychotic thrown in? Or do they depend on the parents to report in their 10-minute interviews each month or so? Do psychotherapists measure something “objective” and demonstrate that it has changed as a result of their ministrations? None that I saw ever did, but perhaps the field has changed. The client is the judge–even subjectively–of the result.

In fact, because I have worked with a lot of parents and self-trainers, I guess I’ve seen a number of examples that went in exactly the opposite direction. One of the first clients I worked with was a 9-year-old girl on Ritalin who had tried to go off it during her second semester and nearly ended up failing the year. The parents spoke to her physician about NF, and he was frankly dismissive. The girl trained over the summer, around 40 sessions, and went back to school in the fall without the Ritalin. She ended up on the honor roll for the first time in her life. When the parents returned to the physician with this news–rather objective I would say–he told them the NF had nothing to do with it, and that sometimes children simply “grew out” of ADHD.

TOVA

Speaking of “objective” measures like the TOVA or IVA: I tried both (the TOVA twice), meaning that I bought them and charged my clients for my use of them for several months one time and a bit less than a month the second time.

First time I threw the TOVA away when, after spending 22 minutes in a darkened room with a kid who did everything but climb up on the table and was holding the micro switch by the cable and swinging it against his leg to “press” the button–during which time I eased my frustration with the belief that at least this kid would have the highest scores ever recorded–the result which I got to take to his parents was that he was “within normal limits”! I promised never again to charge them for another TOVA and we went on with training which, after about 40 sessions, demonstrated some changes with which they were happy (didn’t do another TOVA to see if he was still “normal”).

Later that year I ran into a physician who was hyping for the TOVA at the Winter Brain conference, and I told him my experience. He told me with a sheepish grin, “Yeah, that can happen. You have to adjust for intelligence sometimes.” I told him I must have missed that part of the instructions, and he told me, “oh, it’s not a formal adjustment.”

The second time I threw it away (after buying IVA and TOVA to compare them a few years later) was after presenting parents with an impressive report on the improvements from pre/post TOVA on their kid. They went off on me. The father told me they were still getting called 4-5 times a week by the kid’s teacher to complain about his classroom behavior, it still took hours every night to get his homework done, they still couldn’t let him out of their sight because he was so impulsive that he did dangerous things without a thought, and they still couldn’t take him to church and he still wasn’t getting invited to birthday parties. “I don’t care what the damned test shows!” And I agreed 100%. Didn’t see much, if any, change in him. They hadn’t paid me to improve his TOVA scores, and what they had paid me to do hadn’t happened.

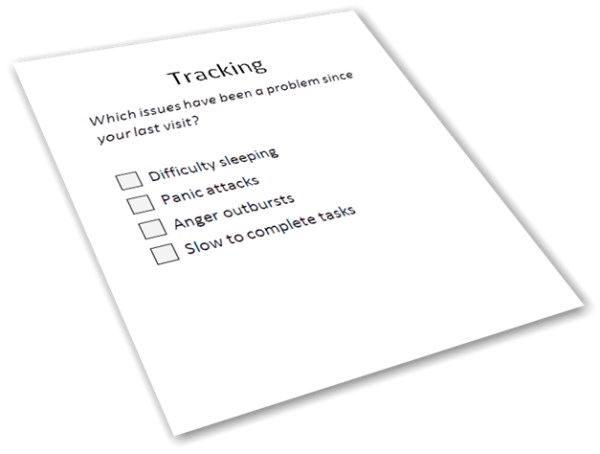

So it’s not so hard to objectively track results. How many panic attacks did you have this week? How many nights where it took you more than 20 minutes to sleep? How many calls/notes from the teacher? How long did his homework take? How many seat assignments were brought home because they were not completed?

Reassessment

I don’t do reassess with any of my clients, except in cases where the first assessment was of someone who was heavily medicated and they have stopped the meds. In such cases it’s not unusual to see an EEG that appears to have nothing to do with the symptoms the client wants to change. Taking away the meds allows the “real” brain patterns to appear.

It may help to think of an assessment as a snapshot of someone jumping on a trampoline. If you take two pictures a month apart, can you say with any confidence that the client is jumping higher? Of course not. She may have been on the way down in the first photo and near the top of the jump in the next. Surely you’ve looked at enough EEG’s on a power spectrum to recognize that the fantasy of those who don’t deal with the EEG regularly–i.e. that the brain can be “in” alpha or “in” beta–is just a fantasy. Every brain is in alpha and beta and theta and delta all the time, with different emphases depending on the site, the task in process and, yes, environmental factors like Big Macs.

The TLC, unlike a Q, does not compare the brain against a “normative” database. If we assume that a poet and an accountant are likely to have very different brain activation patterns, which one is “normal”? Instead the TLC takes advantage of excellent work that has been done by many QEEG researchers–yes, including Sterman, Lubar, Gurnee, and others–who have studied groups of people who share the same difficulties in mood/behavior/performance and noted that there is a greater tendency on their part to have a specific variation from what is found in the “normal” databases.

The TLC focuses on comparing the brain against itself: Does it produce and block alpha and where and when? How is beta over the left hemisphere related to beta over the right, etc? The assessment allows me to look at a brain and say (always allowing for the fact that there may be artifact if I didn’t actually gather the samples myself) that frontal coherences in fastwaves appear quite high, and that would be expected to result in a kind of mental rigidity, perhaps obsessiveness and often anxiety. Without an assessment I’d have no way of knowing that pattern existed. And I can be pretty confident that, if the bouncing trampolinist has long hair and skinny legs in one photo, he’ll probably have them in others taken around the same time. The brain changes, speeds up, slows down, etc. over a day and depending on food, sleep, etc. But these energy relationships tend to remain pretty stable. That said, however, I know from years of experience that some percentage of people complaining of anxiety who show high fastwave cohernece in the frontal lobes will be successful in training it down, and when they do they will experience a positive change. I also know that some percentage won’t be able to budge it much–and some who do still won’t “feel” much having done so.

So the TLC is oriented not toward providing the the 1 magical protocol which will transform the client. I’m not aware of anything that can do that given the blessed individuality of brains. Instead it gives me 3-5 sets of protocols/placements I can test that could be expected to move that client in a positive direction. I test each grouping in a session and watch for effects in the following 12-24 hours, and after I’ve tried them all, then we decide on which one to pursue.

Reassessment to Prove Efficacy

If you need an assessment to tell you if the training is working…it’s not. If you are hoping to prove that the training worked with the EEG, you’ll probably be disappointed. The assessment or the Q could be done several times over a period of a couple days and come up looking quite different depending on whether it was done early in the morning, after lunch, late afternoon, during the school/work year, during summer vacation, etc. So if you see changes, are they the result of training–or a big mac with fries half an hour before the data gathering.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –